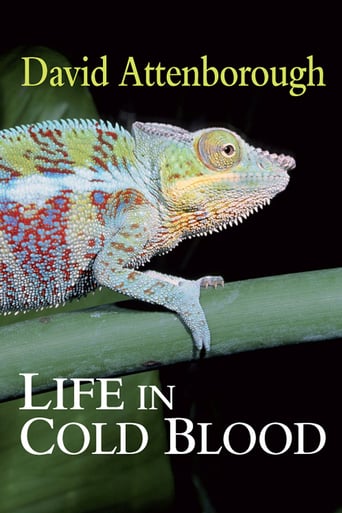

Life in Cold Blood Season 1

David Attenborough reveals the surprising truth about the cold-blooded lives of reptiles and amphibians. These animals are as dramatic, as colourful and as tender as any other animals.

Watch NowWith 30 Day Free Trial!

Life in Cold Blood

2008 / TV-G

David Attenborough reveals the surprising truth about the cold-blooded lives of reptiles and amphibians. These animals are as dramatic, as colourful and as tender as any other animals.

Watch Trailer

With 30 Day Free Trial!

Life in Cold Blood Season 1 Full Episode Guide

The final programme covers the most ancient of the reptiles: the crocodiles and turtles. In the Galápagos Islands, among the giant tortoises, Attenborough explains how the creatures came to develop their shells as a defence against predators. This is demonstrated by the eastern box turtle, whose shell includes a hinged 'drawbridge'. The aquatic pig-nosed turtle is unusual in that its eggs need to be submerged before hatching, whereas those of other species would drown; Attenborough illustrates this by dropping an egg into a jar of water: it immediately hatches. In the open ocean, male sea turtles attempt to separate a rival from its mate by attacking and overwhelming the pair, stopping them from taking in air. In northern Australia, Attenborough observes a large gathering of crocodiles at a flooded coastal road: they time their arrival to ambush migrating mullet. The complex communication and body language of the American alligator is investigated and in Argentina, the calls of young caimans help their mother locate and lead them to a nursery pool. The mother's maternal instinct extends to releasing unhatched babies by gently crushing their eggs in its jaws. In Venezuela, a female spectacled caiman in charge of an entire crèche leads the infants from a drying river bed on a trek to permanent water

The fourth episode focuses on the most modern reptiles, the snakes, exploring how they have managed to become successful despite their elongated body shape. Attenborough explains how they evolved from underground burrowers to surface hunters, losing their limbs in the process. With the aid of infrared cameras, a timber rattlesnake is shown lying in wait for a mouse and sensing its repeated path before despatching and eating it. A snake's constantly flickering tongue is used to gather and evaluate the molecules of its surroundings, and Attenborough visits Carnac Island to witness a population of blind tiger snakes, which feed on the chicks of nesting gulls. He also confronts a Mozambique spitting cobra, which quickly sprays venom over the presenter's protective face visor. The similarities in colouration between the harmless kingsnake and potentially lethal coral snake are highlighted. An example of a snake that can tackle unusual prey is the Queen snake, which almost exclusively hunts newly-moulted crayfish. A pair of rival male King cobras are seen battling and infant cobras are shown hatching: their venom is immediately as fatal as that of their parents. In Argentina, a yellow anaconda evades nearby caimans to give birth to live young. Finally a turtle-headed sea snake feeds not on fish, but on their eggs laid on a coral reef

The third instalment takes a look at the immense diversity, social skills and displays of the lizards. While they are highly adept at camouflage, occasionally there is a need to break cover in order to ward off rivals. Attenborough holds up a mirror to an anole and causes it to extend its colourful throat flap as a warning sign. Madagascar is host to over 60 species of chameleon but one of the largest, Meller's chameleon, is native to Malawi and two rival males are shown jousting. A female South African dwarf chameleon demonstrates its ability to change colour when communicating to a potential mate, and the chameleon's muscular tongue is depicted lassoing its prey. In southern Australia, Attenborough uses a baited fishing rod to attract the attention of a rare pygmy bluetongue skink, thought to have been extinct for over thirty years until it was rediscovered in 1992. Shinglebacks are among the most devoted lizards and breeding pairs can reunite each year for up to two decades. Alongside South Africa's Orange River, large groups of flat lizards feed on the swarms of black flies, but the males also use the occasion to indulge in social squabbling. The Mexican beaded lizard is one of the few with a poisonous bite, but males do not employ it when wrestling each other. Finally, Attenborough comes face to face with a perentie, Australia's largest monitor lizard. Under the Skin focuses on filming in Australia.

The second programme explores the world of amphibians, of which there are some 6,000 known species. Attenborough visits Australia to illustrate how they became the first back-boned creatures to colonise land: the lungfish, which is capable of breathing air, and whose ancestors became the first amphibians. The largest of them is the Japanese giant salamander and two are shown wrestling for territory. In North America, the marbled salamander spends most of its life on land, yet is still able to retain the necessary moisture in its skin through the damp leaf litter. A female caecilian is filmed with her young, whose rapid growth is discovered to be the result of eating their mother's skin — re-grown for them every three days. The most successful amphibians are frogs and toads. Their calls are most active during the breeding season: females are impressed by both volume and frequency. However, gestures are sometimes needed and the poisonous Panamanian golden frog uses a conspicuous form of 'semaphore'. Most other frogs rely on camouflage and the South American red-eyed tree frog is an example. An African bullfrog is shown defending its exposed tadpoles by digging a canal for them. Meanwhile, the male marsupial frog keeps its young moist by carrying them in its skin pouches. Under the Skin examines the filming of the last population of Panamanian golden frogs, which is threatened by a fungal disease.

The first episode discusses the keys to success of reptiles and amphibians, looking at thermoregulation, parental care and the time-scales on which reptiles operate.

Free Trial Channels

Seasons