Justice Season 1

With 30 Day Free Trial!

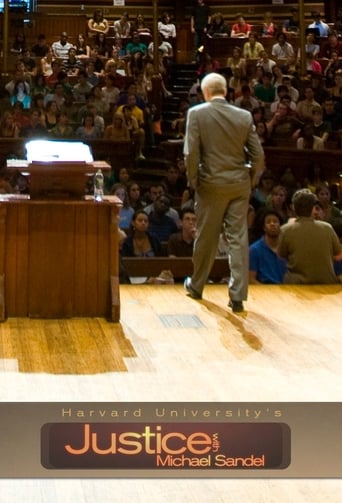

Justice

2009

Justice is the first Harvard course to be made freely available online and on public television. In this 12-part series, college professor Michael Sandel challenges us with hard moral dilemmas and invites us to ponder the right thing to do—in politics and in our everyday lives.

Watch Trailer

Justice Season 1 Full Episode Guide

If principles of justice depend on the moral or intrinsic worth of the ends that rights serve, how should we deal with the fact that people hold different ideas and conceptions of what is good? Can we settle the matter without discussing the moral permissibility of homosexuality or the purpose of marriage? Sandel believes government can’t be neutral on difficult moral questions, such as same-sex marriage and abortion, and asks why we shouldn’t deliberate all issues—including economic and civic concerns—with that same moral and spiritual aspiration.

Communitarians argue that, in addition to voluntary and universal duties, we also have obligations of membership, solidarity, and loyalty. These obligations are not necessarily based on consent. We inherit our past, and our identities, from our family, city, or country. But what happens if our obligations to our family or community come into conflict with our universal obligations to humanity? Do we owe more to our fellow citizens that to citizens of other countries? Is patriotism a virtue, or a prejudice for one’s own kind? If our identities are defined by the particular communities we inhabit, what becomes of universal human rights?

Aristotle believes the purpose of politics is to promote and cultivate the virtue of its citizens. The telos or goal of the state and political community is the “good life”. And those citizens who contribute most to the purpose of the community are the ones who should be most rewarded. But how do we know the purpose of a community or a practice? How does Aristotle address the issue of individual rights and the freedom to choose? If our place in society is determined by where we best fit, doesn’t that eliminate personal choice? What if I am best suited to do one kind of work, but I want to do another?

Students discuss the pros and cons of affirmative action. Should we try to correct for inequality in educational backgrounds by taking race into consideration? Should we compensate for historical injustices such as slavery and segregation? Is the argument in favor of promoting diversity a valid one? How does it size up against the argument that a student’s efforts and achievements should carry more weight than factors that are out of his or her control and therefore arbitrary? When a university’s stated mission is to increase diversity, is it a violation of rights to deny a white person admission? Sandel introduces Aristotle and his theory of justice. He believes that justice is about giving people their due, what they deserve.

Rawls argues that even meritocracy—a distributive system that rewards effort—doesn’t go far enough in leveling the playing field because those who are naturally gifted will always get ahead. Furthermore, says Rawls, the naturally gifted can’t claim much credit because their success often depends on factors as arbitrary as birth order. Sandel discusses the fairness of pay differentials in modern society.

Immanuel Kant believed that telling a lie, even a white lie, is a violation of one’s own dignity. Sandel introduces the modern philosopher, John Rawls, who argues that a fair set of principles would be those principles we would all agree to if we had to choose rules for our society and no one had any unfair bargaining power.

Professor Sandel introduces Immanuel Kant, a challenging but influential philosopher. Kant rejects the notion that morality is about calculating consequences. When we act out of duty—doing something simply because it is right—only then do our actions have moral worth.

During the Civil War, men drafted into war had the option of hiring substitutes to fight in their place. Many students say they find that policy unjust, arguing that it is unfair to allow the affluent to avoid serving and risking their lives by paying less privileged citizens to fight in their place. Is today’s voluntary army open to the same objection? Professor Sandel examines the principle of free-market exchange as it relates to reproductive rights. Students debate the nature of informed consent, the morality of selling a human life, and the meaning of maternal rights.

The philosopher John Locke believes that individuals have certain rights—to life, liberty, and property—which were given to us as human beings in the “the state of nature,” a time before government and laws were created. According to Locke, our natural rights are governed by the law of nature, known by reason, which says that we can neither give them up nor take them away from anyone else.

Sandel introduces the libertarian notion that redistributive taxation—taxing the rich to give to the poor—is akin to forced labor. If you live in a society that has a system of progressive taxation, aren’t you obligated to pay your taxes? Don’t many rich people often acquire their wealth through sheer luck or family fortune?

Sandel presents some contemporary cases in which cost-benefit analysis was used to put a dollar value on human life. The cases give rise to several objections to the utilitarian logic of seeking “the greatest good for the greatest number.” Is it possible to sum up and compare all values using a common measure like money?

If you had to choose between killing one person to save the lives of five others and doing nothing, even though you knew that five people would die right before your eyes if you did nothing—what would you do? What would be the right thing to do?

Free Trial Channels

Seasons