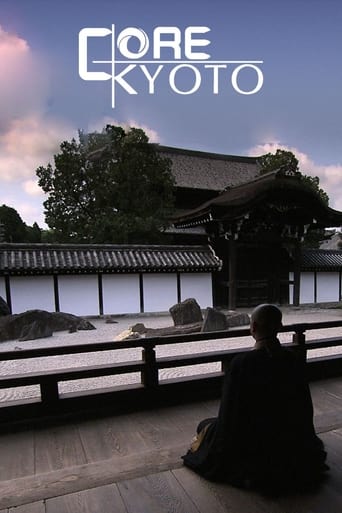

Core Kyoto Season 1

The timeless heart of Japan's ancient capital. Against its rich backdrop of culture and tradition, today's Kyoto continues to innovate and inspire.

Watch NowWith 30 Day Free Trial!

Core Kyoto

2013 / NR

The timeless heart of Japan's ancient capital. Against its rich backdrop of culture and tradition, today's Kyoto continues to innovate and inspire.

Watch Trailer

Core Kyoto Season 1 Full Episode Guide

The changing leaves vividly color Kyoto, which lies in a basin and has marked temperature differences. For more than a millennium, people have delighted in their beauty and picnicked under the trees. Today, the changing leaves continue to enchant Kyotoites, who live within the changing seasons. The exquisite leaves adorn traditional kaiseki cuisine dishes, and the trees lit up at night are a magical sight. Some are so captured by their magnificence they express it in waka poetry and the arts.

The ancient capital has many shinise, or established businesses, with unbroken histories. Kyoto Prefecture classes a firm founded at least a century ago as shinise. Over generations, more than 1,100 Kyoto shinise have maintained imperial court culture and life; and provided for temples, shrines, samurai clans and the common people. Through the ups and downs, they have upheld their trade, reputations and family mottos; and kept the Kyoto entrepreneurial spirit of status and trust alive.

Nishijin-ori symbolizes the ancient capital's elegance and luxury. The obi-weaving process is divided into detailed tasks, such as mon-template design and yarn dying. Each artisan has a specialist role. With a deep sense of responsibility and a mutual trust, they strive for higher levels of perfection. Noh costumes have unsurpassable beauty. Some artisans weave with their fingernails. This magnificent textile meshes the city's 1,200 year-old history and the fervor of artisans through the ages.

A pointed boulder with a large stone at its foot reaches for the heavens. The white gravel between them represents a swift flowing river, without the use of water. Karesansui is a unique dry-gardening style that developed in the 14th century from ascetic practices at Kyoto's Zen temples. Monks aim for enlightenment within a world of rippling patterns that run between curious rock arrangements. Enter the infinite Zen cosmos through the karesansui gardens at Tenryu-ji, Daisen-in and Ryoan-ji.

As demand for lacquerware grew in the political and cultural hub of Kyoto, artisans refined their designs and techniques with a distinctive approach to aesthetic beauty. This became kyo-shikki, or Kyoto-style lacquerware. The maki-e drawing technique uses sprinkled gold dust on a jet-black background to reproduce dazzling Kyoto scenes. Modern sensibilities combined with traditional techniques produce innovative pieces. Lacquer and gold dust engender the lavish world of this traditional craft.

Kyoto has many mountain springs, rivers and groundwater. The capital relocated here about 1,200 years ago for the water supply that enriched the citizens' lives and gave rise to Kyoto's culture. Farmers grow vegetables in the fertile delta. Craftspeople continue the kurozome dying traditions. A namafu wheat-gluten store relies on quality groundwater. Supporting them are well sinkers with an extensive knowledge of groundwater arteries. Ever grateful, the locals use water as their livelihood.

In the 1200's, the monk Dogen brought shojin-ryori, a vegetarian cuisine, from China along with Zen Buddhism, which forbids the killing of animals and the eating of meat. He once said, "Meals and their preparation are part of aesthetic training". Kaiseki-ryori and other Japanese cuisine have their base in and developed from shojin-ryori, which wastes nothing of the seasonal vegetables and cereals used. Chefs, including a chef at a Michelin-rated restaurant, work to spread shojin-ryori worldwide.

Gion Matsuri began as a prayer for the country's health when 66 halberds were erected and 3 mikoshi shrines were paraded through plague-ravaged Heian-kyo in 869. The 33 yamahoko floats in today's climactic procession on July 17 are "moving museums". Revived in 1952, the Kikusui-hoko float was adorned this year with a new tapestry in gratitude to the ancestors. The festival music is traditionally taught orally. The floats are assembled with age-old technics. The streets are alive with revelry on the eve of the parade.

Sen-no-Rikyu (1522-1591) began the chanoyu, or tea ceremony, that is practiced today, 400 years ago. His simple, rustic wabi philosophy is still discernable in the designs, movements and mindset. In Uji, Kyoto, the year's first shoots from shaded tea plants are ground into a fine powder to make the koicha tea used in the ceremonies. Artisans use time-honored methods to craft the chanoyu utensils. People immerse themselves in this art in which each bowl of tea is considered a once in a lifetime encounter.

The origin of Aoi Matsuri, one of Kyoto's 3 great festivals, goes back more than 1,500 years. Diviners advised the people to ride horses in prayer for bumper crops and to appease the Kamo deities, who were causing storms and floods. Emperors thereafter paid homage to Shimogamo Jinja Shrine and Kamigamo Jinja, and solemnly performed these now-ancient rituals that are reminiscent of the dynastic culture. Aoi Matsuri, its splendid parade and rare customs are full of mystery, even for Japanese.

The main stage for hospitality in the glittering kagai entertainment district is the ozashiki function. Geiko and maiko refine their skills over years in dance and other performing arts to present at ozashiki. In this world, shikitari customs and etiquette are dictated by strict protocol drilled into the girls by their elders in their daily lives. A shidashiya caters meals for ozashiki. A yuzenshi dyer creates unique maiko kimono. Many people live within the culture at the heart of the kagai.

The quality of hospitality found at accommodations in Japan's old capital, Kyoto, is known worldwide. They exude a time-honored culture and uniqueness. The entrances are cleansed with sprinkled water and the rooms have peaceful atmospheres with a seasonal touch of flowers. This ingrained sensibility is drawn from Shinto and Buddhist teachings. Once billeting monks, a Zen temple offers pilgrims' lodgings - the roots of Kyoto lodgings. Established inns uphold their founding standards. The essence of consideration that soothes travelers exists in diverse lodgings around the city.

Japanese-style paintings are the embodiment of Kyoto aesthetics. Their delicate scenes are created using unique mineral pigments. Flower artist Rieko Morita emphasizes life in her work. She infuses it with the vitality she feels within the flowers. Modern artists, like her, are grounded in a history that stretches back 1,000 years to the dynastic paintings of the Heian Period. All kinds of schools with distinctive styles were born throughout the long history. The Kano School of painting was favored by samurai. The Rimpa School was characterized by decorativeness. The Maruyama School stressed realism. Various traditions give Kyoto paintings diversity and allure.

Various locations in Kyoto have been famous cherry-blossom-viewing spots for 1,200 years. As spring approaches, the locals' actions revolve around thoughts of hanami. The cherries keep family ties strong; 3 generations gather once a year for hanami festivities. A 3rd-generation cherry gardener who conserves cherry trees and a photographer who has snapped Kyoto's cherries for about 40 years talk about the enduring allure of these flowers, which feature in bento meals and embroidery designs.

Kyoto has about 2,700 temples where an array of benevolent, meek, and ferocious Buddhist statues are worshipped. World Heritage temple Toji has a configuration of statues in an imposing, 3D mandala and a beautifully woven mandala, which captures the cosmos. The jizo statues standing on street corners have a special place in the lives and hearts of Kyotoites. Today, sculptors continue to breathe life into Buddhist statues, and skilled craftsmen create magnificent works using gold leaf in microns.

Stimulating all five senses, kaiseki-ryori is a Kyoto culinary work of art. Eiichi Takahashi, 14th generation owner of Hyotei, stresses kaiseki's roots in cha-kaiseki meals served at tea ceremonies. Leading chefs and researchers explore new potential for kaiseki. Takuji Takahashi, 3rd generation owner of Kyo-ryori Kinobu, creates novel dishes using Western methods while preserving the form of Japanese cuisine. These inquisitive minds pursue the ultimate in culinary hospitality.

Kyotoites have lived in kyo-machiya townhouses for centuries. Each year, 1,000 are demolished, but Kyo-machiya Sakujigumi, a group of craftsmen skilled in machiya restoration, use natural materials and traditional methods to preserve them. Megumi Hata, whose family kyo-machiya was built in 1869, discusses how living in a machiya means living comfortably in harmony with nature. Within their walls, the wisdom, the way of life and the spirit of Kyotoites remain unchanged through the generations.

Free Trial Channels

Seasons